I love myths. I have for as long as I can remember. Myths are traditional stories, especially ones that are concerning with the early history of specific groups of people and give insights into natural or social phenomenon. This can often involve supernatural beings or events, which is pretty much fantasy too. Myths from different locations share a lot of things in common, across the miles and the years – as does crime, but we’ll get to that.

The tales about King Arthur and his Round Table are based in myth and legend too – the difference between that legends potentially have an historical basis. If any story has been more continuously reinvented, from the days of Thomas Mallory’s Le Morte d’Arthur to teen-appeal TV, I don’t know of it. Mark Twain even put ‘A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court’

So, I wondered, some time ago now, whether Camelot was ripe for yet another reinvention? A reinvention that involved a little more crime, that in essence was a touch more Noir? ‘Camelot Noir’ – it certainly has a ring to it!

I realised straight off that this was not the sort of book to appeal to genre purists of course, let alone those who think that intertextuality should be banned and books, movies, plays, songs and games must all stay in their separate boxes. I don’t. I worship at the altar of intertextuality, nothing excites me more – witness my not getting to sleep when I discovered something exciting about the fabulous ‘Pennyworth’ TV series last night (but that’s another blog!). And these classifications are breaking down all over the place and, as a film scriptwriter as well, I love playing with genres: crime and fantasy, myths and murder – well it went on all the time, didn’t it?

There is one major question to be answered though; are the basics necessary for crime fiction present in such a myth? It’s a very important question as well. Fortunately I had some help in answering it. Crime writer, and former police officer, Clare Mackintosh has put together a 10-point checklist that or us to cover the subject matter.

Here are what Clare suggests are the essentials of crime fiction and what I believe ‘Camelot Noir’ offers.

A hook

Well, how about being in Camelot without a single shiny knight in sight? Just those ‘mean cobbled streets’ that detectives have always strode down in one guise or another.

Atmosphere.

Camelot would certainly be dark and mysterious enough for a good Noir feel. Camelot could have invented it.

A crime.

The place is lousy with swords, surely a serious crime is almost inevitable. Yes, but the crime has to matter – it can’t be just casual mayhem. That wouldn’t do at all, although such violence can’t be ruled out either.

A victim.

The victim therefore needs to matter – as Lords and Ladies always have done.

A villain.

Oh, myths have plenty of great villains. Camelot is no exception, take your pick.

Red herrings.

When there is a fantasy element the herrings aren’t just red they can fly too. No cheating though, a common problem for ‘detectives’ in science fiction crime novels as well.

Twists and reveals.

How about throwing in an ageless magician with his own agenda? That should do it.

Tension.

The fate of an entire Kingdom and the monarchy should create enough of that.

A satisfying Resolution

With room for a sequel? No problem.

A hero

There are plenty of heroes in Camelot. Rather too many perhaps and they all wear a lot of polished metal and sit round a big Round Table. They’re great in their place but not the right sort of hero we need at all. No, what Camelot needs, to quote Raymond Chandler is a man “who is neither tarnished nor afraid. He is the hero; he is everything. He must be a complete man and a common man and yet an unusual man… He must be the best man in his world and a good enough man for any world. He will take no man’s money dishonestly and no man’s insolence without a due and dispassionate revenge.’ Perhaps he could be called Chaucere? (The extra ‘e’ being a nod Chandler’s Marlowe – see what I did?)

That’s the 10 essential ingredients for crime fiction all ticked then and so I hereby conclude that this Arthurian myth, at least, fulfils the bill.

All that remains is for me to introduce you to our hero Chaucere. A man with a great sense of fair play for all people, not just those in the Big House on the Hill. A sword that was ‘for hire’ for many years in many different places, before our man’s feet led him back to the place of his birth and a secret he dare not reveal, less a Kingdom falls before it rises. He lives in the less elegant environs of a Camelot you won’t have seen before. This, after all, is ‘Camelot Noir’.

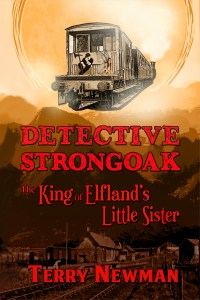

It’s just a crime novel really, with magicians, a well-known King and a famous sword. It’s published by Monkey Business, an imprint of Grey House in the Woods.

Reference

10 essential ingredients for crime fiction by Clare Mackintosh